In 2018 I wrote an article about ceramic blades where I showed that the brittleness of the material (Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia – YSZ) makes it difficult to produce a refined, keen edge and that there is little value in doing so as it will microchip quickly with use. The appeal of ceramic knives is not their ability to take or hold razor keen edge, but rather that they keep an acceptably performing edge for a very long time.

Early in 2021 there was interest in a new ceramic knife material being utilized for kitchen knives. “Elastic Ceramic” or “High Impact Ceramic” addresses one of the issues with traditional ceramic knives in that they can break or shatter due to their inherent brittleness. Impact resistance refers to the idea that the bending strength of a ceramic deteriorates after an impact, due to defects created by the impact. The modified microstructure of the impact resistant ceramic reduces the propagation of cracks due to these defects.

Harcane Industries (Powder Injection Molding feedstock manufacturer) sells these knives through their webshop: Rahven Knives. Harcane lists two versions of High Impact Ceramic – white (20% alumina) and black (<1% alumina) with the same plate toughness (14 MPa.M1/2), bending strength (1350MPa) and impact resistance. Their knives are only available in the black version.

Saint Gobain ZirPro market similar products; white UprYZe™ Ultra-Tough Ceramic or UprYZe-shock™ which contains alumina platelets and UprYZe-black which is described as having improved impact resistance comparable to UprYZe-Shock: (+50% vs. regular yttria doped zirconia), plate toughness of 15MPa.M1/2 and bending strength of >1000MPa. For comparison they quote a toughness of 5.5MPa.M1/2 and bending strength of >1000MPa for their standard 3% Yttria doped Zirconia. Apparently both the alumina platelets and the black pigment lead to improved impact resistance over standard YSZ.

Kyocera now markets two new ceramic knife lines “INNOVATIONblack” (name patented August 2021) and “INNOVATIONwhite” (name patented May 2023) both described as having “2x more durability” than traditional ceramic. Kyocera calls both of these Z212 ceramic (the original YSZ is called Z206). The Z212 ceramic was introduced in 2017 as the Innovation series, originally in black only. Kyocera also sells a “Premier series” blade (2019) which is described as HIP (hot-isostatic press) at 1500C and 2000bar pressure. The HIP Premier blades are also described as having 2x the durability of conventional YSZ.

Two videos from Pete Colligan on his Cedric & Ada YouTube channel in 2021 showed the rope-cutting ability of the Harcane/Rahven HIC ceramic knives outperforming not only a traditional YSZ Kyocera knife but also the gamut of knife steels previously tested. The implication being that the improved macro-scale properties of the material result in micro-scale improvements in edge retention with rope cutting, an abusive task compared to the usual application of ceramic knives in food preparation.

Shortly after these videos were released in 2021, Spyderco knives started looking into manufacturing a test mule from the material. Earlier this year (2024), the first batch of these knives were released for sale. Around that time Sal Glesser (founder and owner of Spyderco knives) contacted me to see if I was interested in having a look at a sample of the material. I agreed, being curious to see how this material compares with the conventional YSZ used in the earlier generation of ceramic knives.

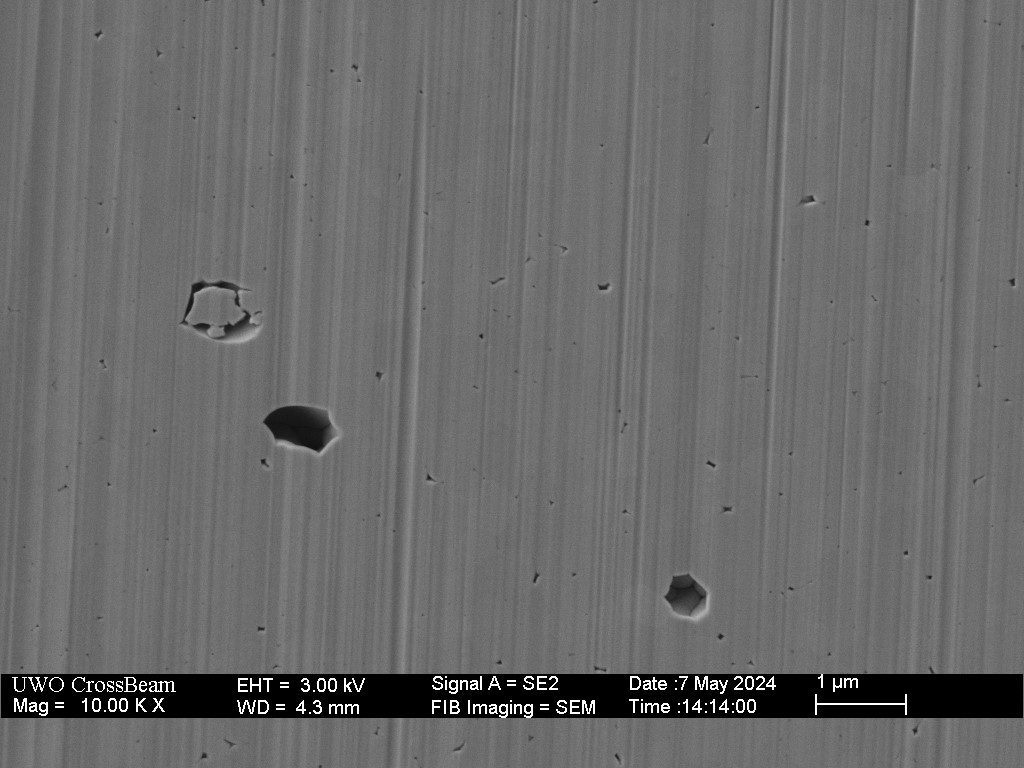

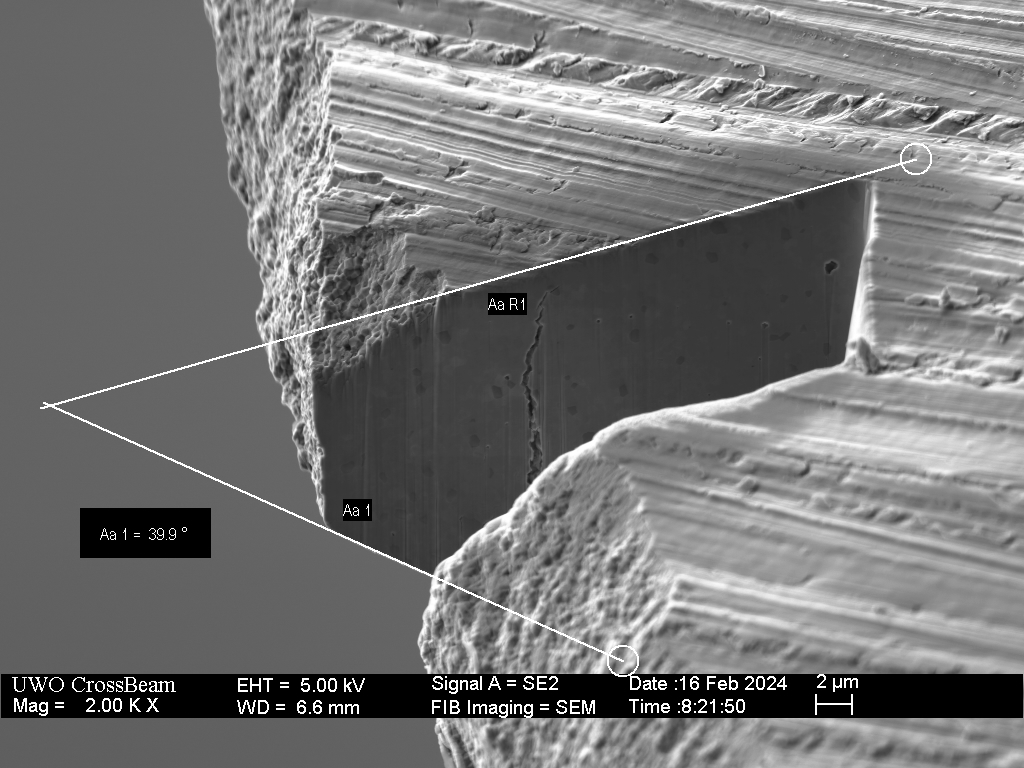

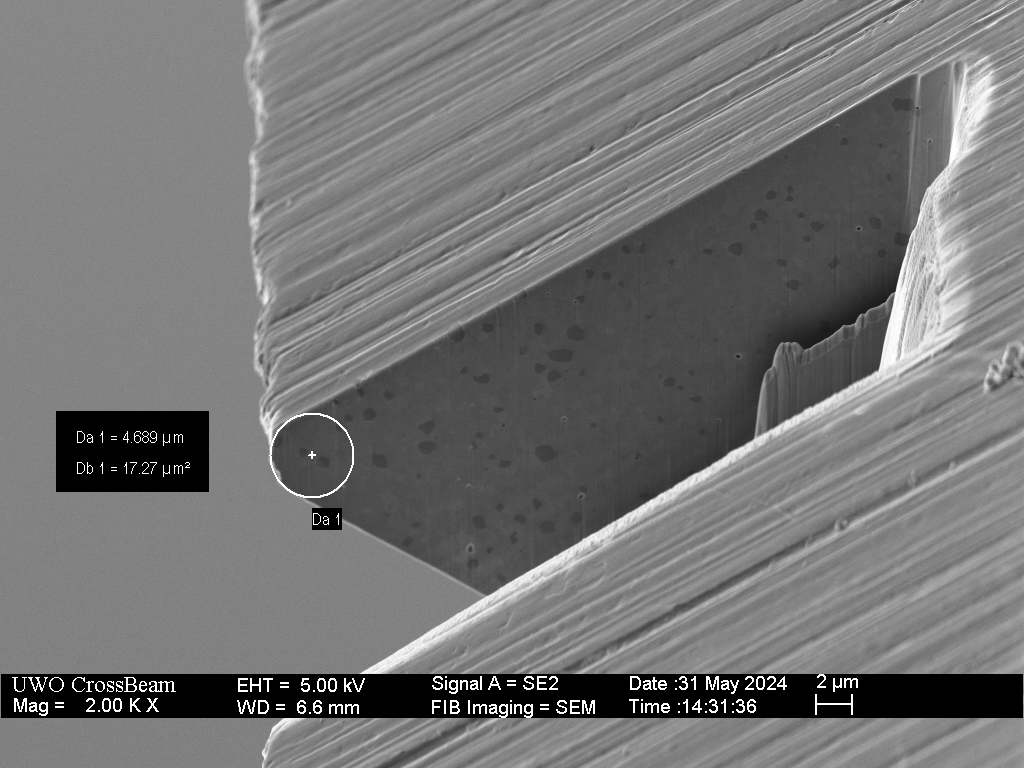

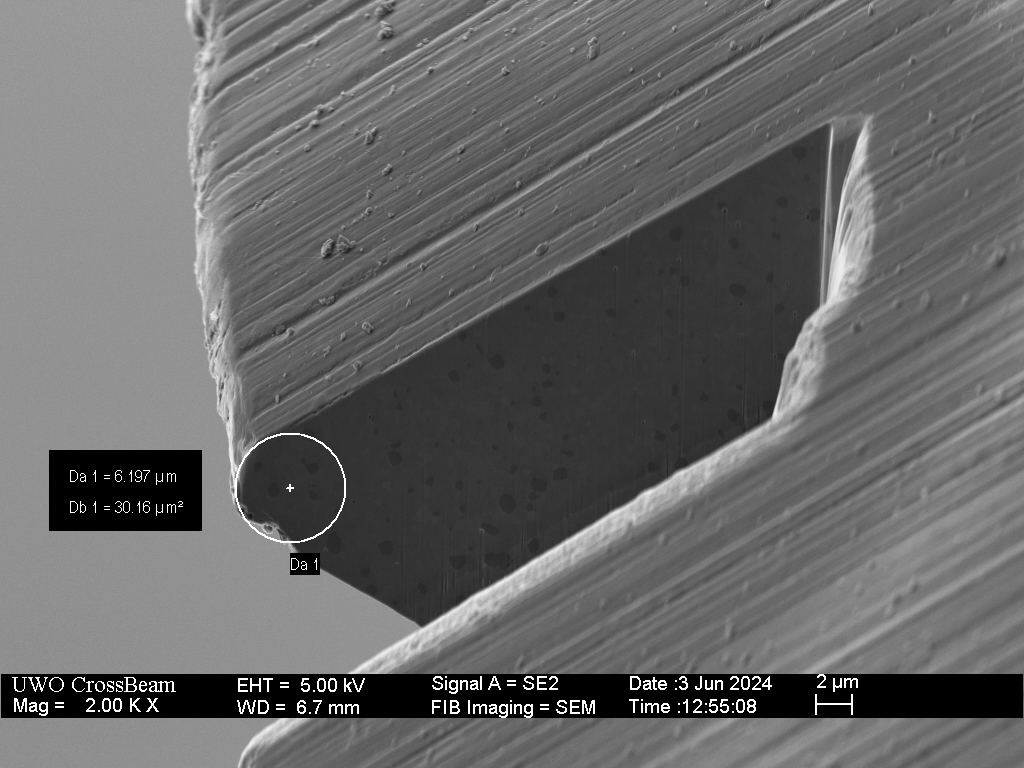

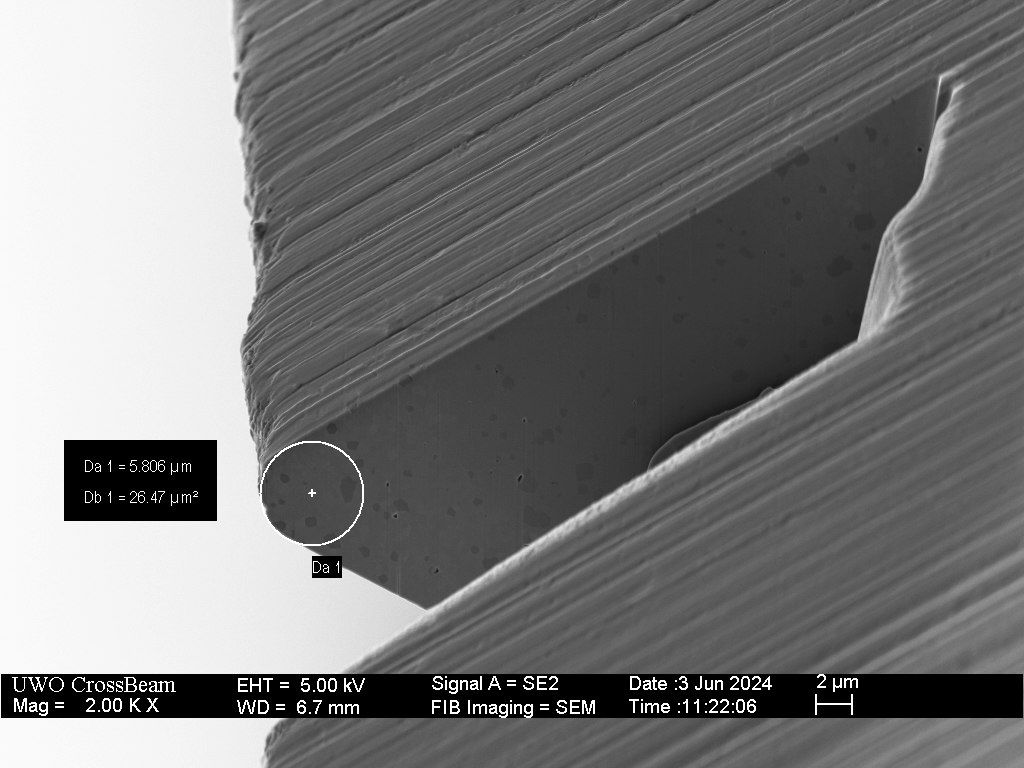

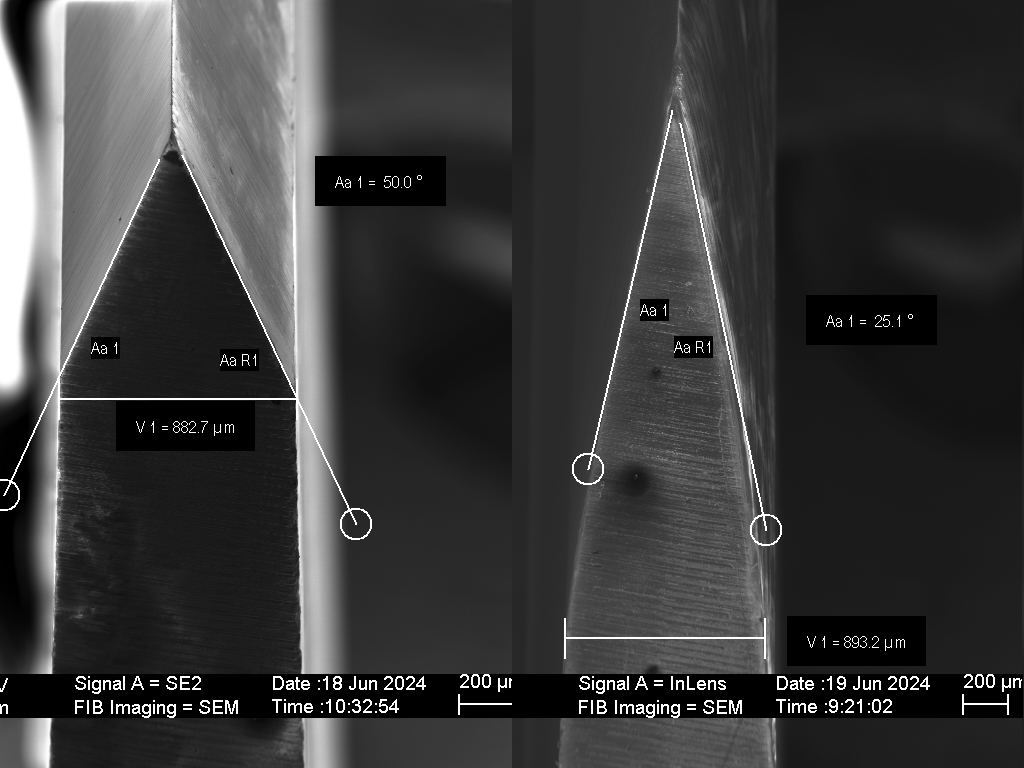

I received two blades from Spyderco with the handles already cut off (the full blade with handle is too large for me to work with). Out of the envelope they seemed quite dull, unable to slice paper. I evaluated this factory edge in the microscope and confirmed it was remarkably dull with a 70 degree included angle near the apex and smooth edge with a radius of more than two microns.

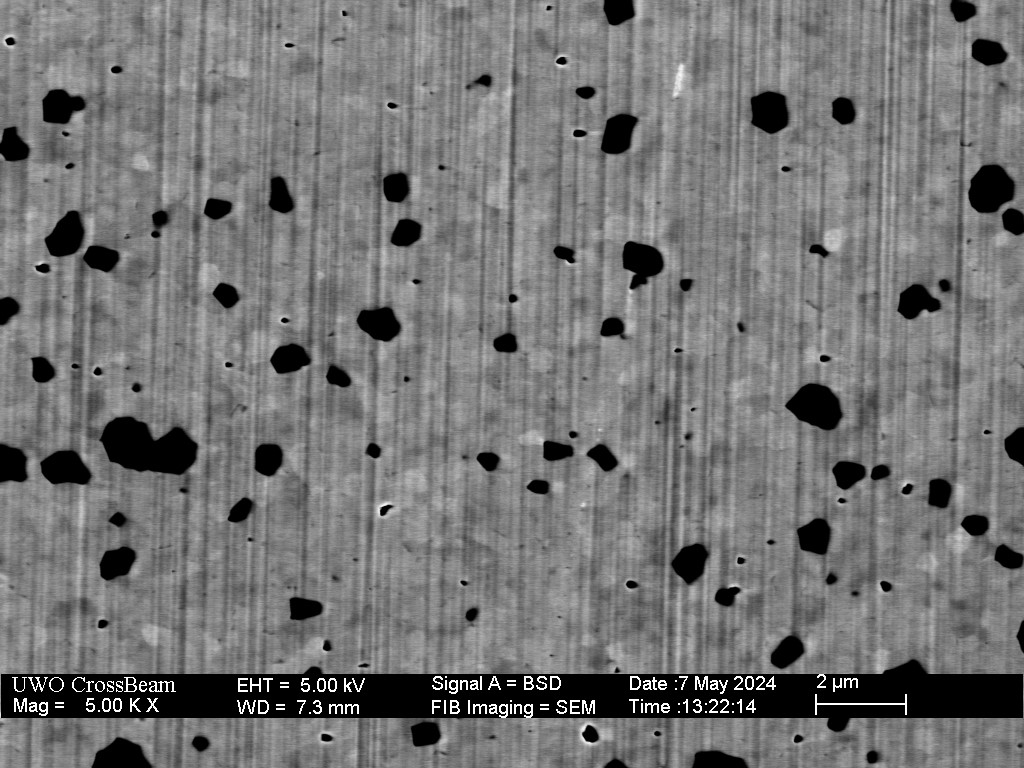

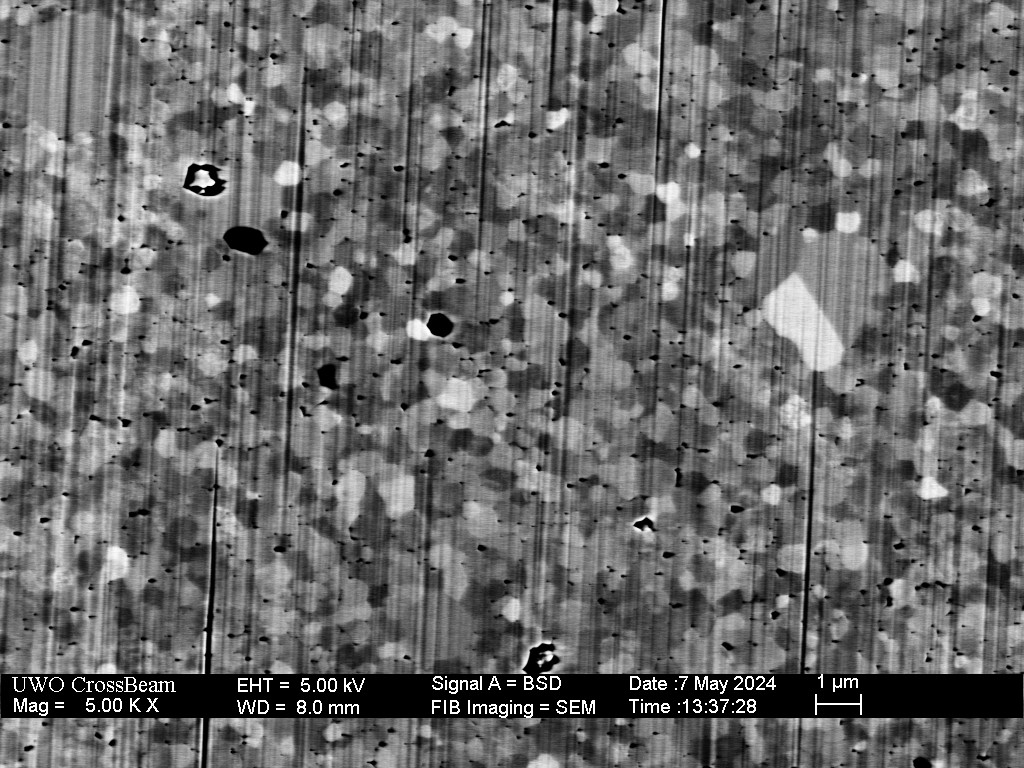

Beyond evaluating the near-edge geometry, the cross-section images (above) show many fewer voids (small spaces between crystal grains) in this material as compared to traditional YSZ as well as some larger dark grains. These differences can be better observed in the next series of images comparing samples of the two materials.

I prepared pieces of each material to evaluate the fractured surface. Anecdotally, the HIC ceramic was observably more difficult to break. While the white YSZ sample was easily broken with nippers, even after sawing most of the way through the HIC blade with a wet diamond saw, it took significant effort to break the last few millimeters. I also polished each sample to compare the grain structure and the presence of voids.

Example SEM images, typical of the two fractured surfaces are shown.

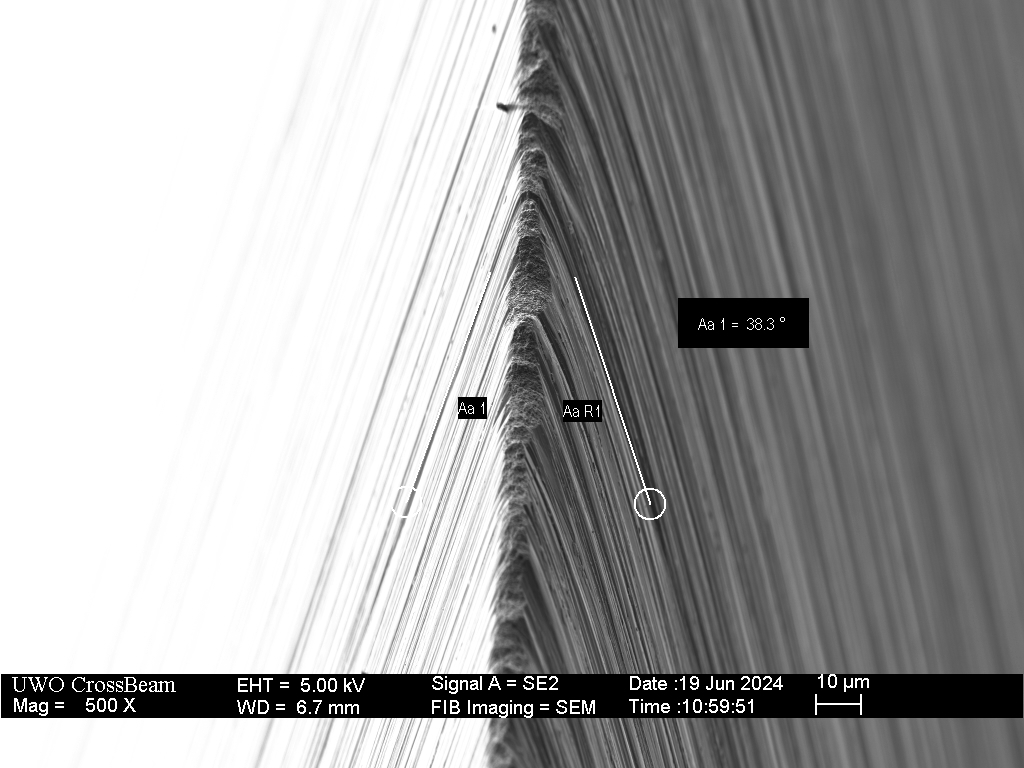

Comparison of the fractured surfaces of the YSZ and HIC ceramic display similar grain size but different micro-texture. The HIC surface appears to have undergone more separation along the margins of the grains (intergranular fracture). The YSZ surface shows more transgranular fracture, leaving a (relatively) smoother surface than the HIC. This observation could explain some of the improved performance of the HIC and is worth further investigation.

The typical ceramic knife apex geometry (with some use) is a fractured surface resulting from micro-chipping. Considering that the rough surface will contribute to slicing aggression, the mechanism of fracture may be as important as the resistance to fracture.

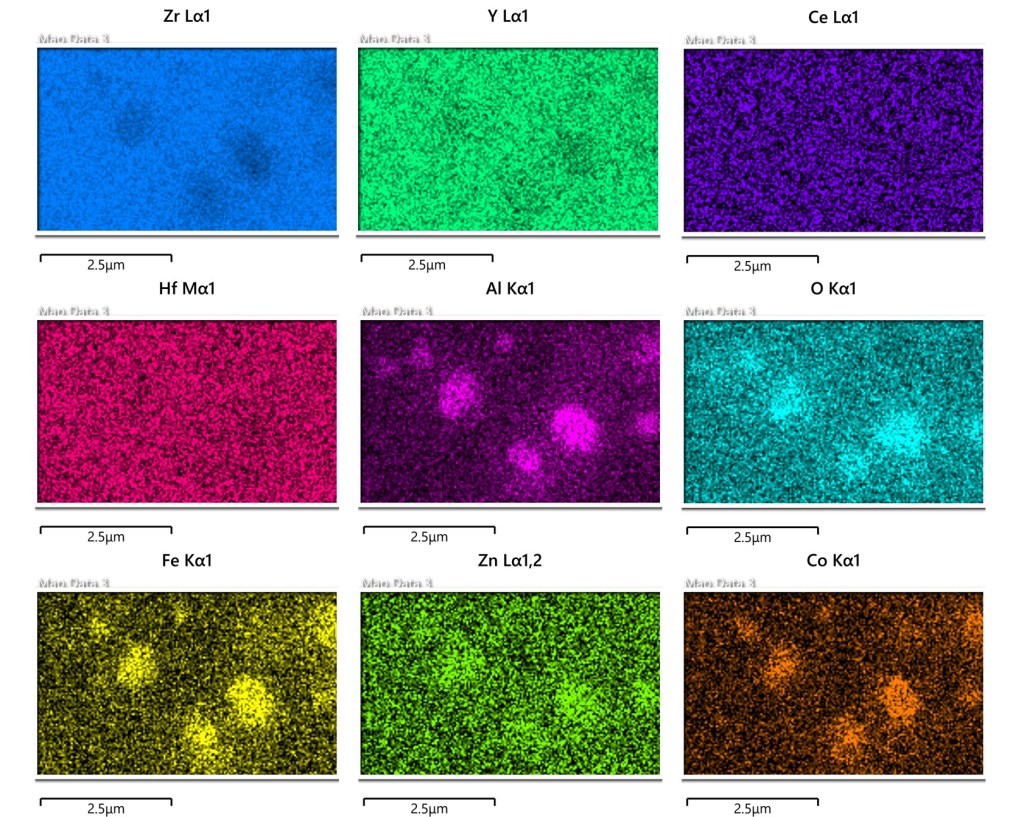

The black HIC sample from the Spyderco mule contains Al/Fe/Zn/Co oxide particles up to one micron in size. These are presumably the source of the black colour. The particles are dark in the backscatter SEM image below, not because of their colour, but because those elements are lighter than zirconium and thus backscatter fewer electrons. The effect of this additive, beyond producing the black colour, on the mechanical properties of the material has not been determined.

To compare the grain structure of the two materials, I imaged their polished surfaces. Beyond the Al/Fe/Zn/Co oxide particles described above, comparison of the two materials shows that the HIC ceramic contains significantly fewer voids than the traditional YSZ.

Bacscatter SEM image of a polished surface of HIC blade material. The s Al/Fe/Zn/Co oxide grains are black in this image as are the small voids.

For comparison, SEM images of a polished region of YSZ ceramic knife material are shown below.

When sharpening a steel blade, ubiquitous burr formation largely preserves the apex from damage during coarse grinding. Ceramic does not form a burr, and therefore requires a different approach to sharpening. Compounding the challenge is that the high hardness of zirconia will rapidly wear aluminum oxide or silicon carbide abrasives, leaving diamond or boron nitride as the abrasives of choice.

As diamond plates do not form an abrasive slurry we might expect less apex damage (chipping) during the grinding process. My experience is that conventional yttria stabilized zirconia knives cannot be sharpened effectively on coarse diamond plates as the edge chips faster than material can be abraded from the bevel, even in the absence of the 3-body damage typically caused by slurry. The images below from the HIC blade sharpened on a DMT F(600) plate show the edge fracture leaves a blunted 10-15 micron wide flat. It seems that coarser diamond plates are no more suitable for the HIC material than they are for conventional YSZ ceramic. Coarse diamond plates can still be useful for thinning the blade, provided another technique is used to hone/refine the apex at a higher angle.

With coarse diamond plates dissapointing, my next attempt was with the coarse Silicon Carbide waterstone: Sigma Power Select II, 240 grit. This is a muddy but fast stone, and although it was able to abrade the ceramic material, the apex also micro-chipped at 20 micron width. Also unfortunate, the stone dished very rapidly during the process.

I conclude that hand sharpening with coarse abrasive produces a broad apex in this material, just as is does in traditional YSZ. The common experience of sharpening steel blades with coarse abrasives where burr formation and refinement provides a convenient pathway is not viable with ceramics as they do not form a burr. However, final honing at a higher angle (15 degrees per side) with fine resin-bonded diamond, diamond lapping film or a diamond belt should be feasible, provided the initial thinning is performed at a low enough angle (for example, 10-12 degrees per side).

Following the above attempts, I was finally succeeded in thinning the Spyderco blade using 3M 15 micron silicon carbide “sharpening” belts on my 1×42 belt sander. These belts had such a short lifespan compared their cost that I do not recommend them for this purpose. While the powered belt did not result in significant chipping, micro-convexity did occur with a significant increase in the angle near the apex

Once the blade has been thinned with these various attempts, I was able to put an acceptable edge on the blade by micro-bevelling with a DMT Extra Fine (1200) diamond plate. The micro-bevel is wide enough to remove micro-convexity and bring the apex angle down below 15 degrees per side.

Without any way to securely hold the cut-off blade I was unable to properly evaluate this knife in use. I did make two tests by slicing approximately 10 meters of corrugated cardboard perpendicular to the corrugations. For comparison, I cut the same amount of this cardboard using a 45 degree draw cut with a new NT cutter snap-off blade.

The key observation is that both the Spyderco Mule and the NT cutter blade had similar apex radius after 10m of cardboard, but the NT cutter was easily outperforming the HIC blade, simply because of the low sharpening angle and the sharpness that results from that geometrical advantage.

I then purchased six small knives from Rahven for additional (future) experimentation. One of the knives was immediately sacrificed for SEM analysis.

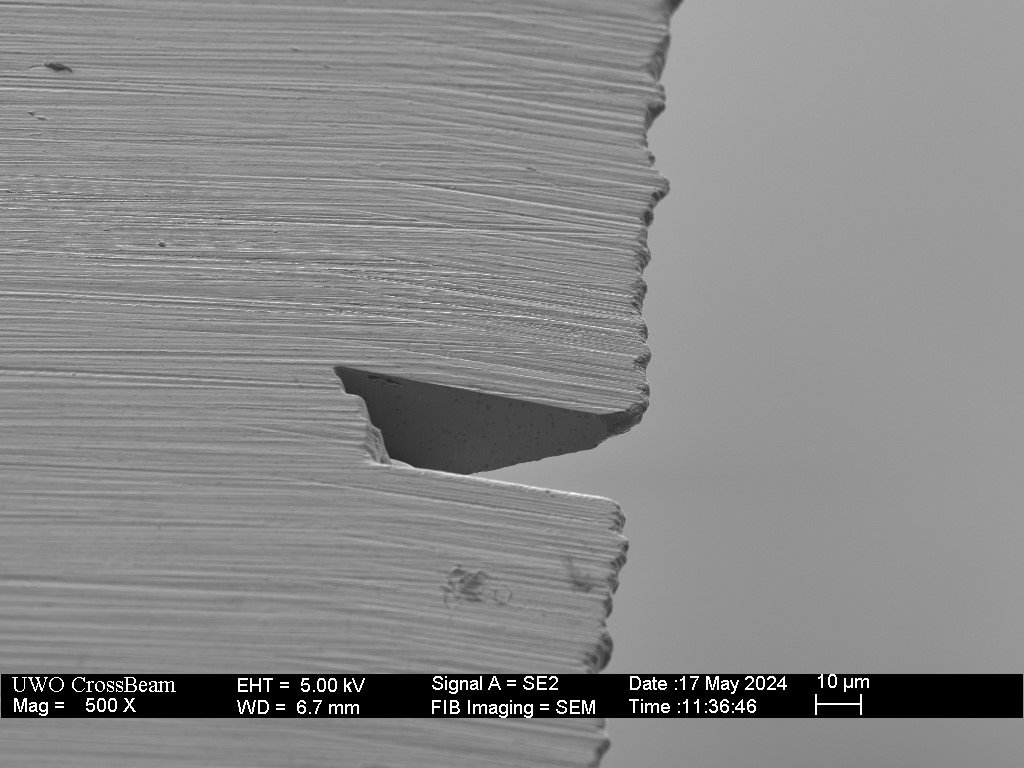

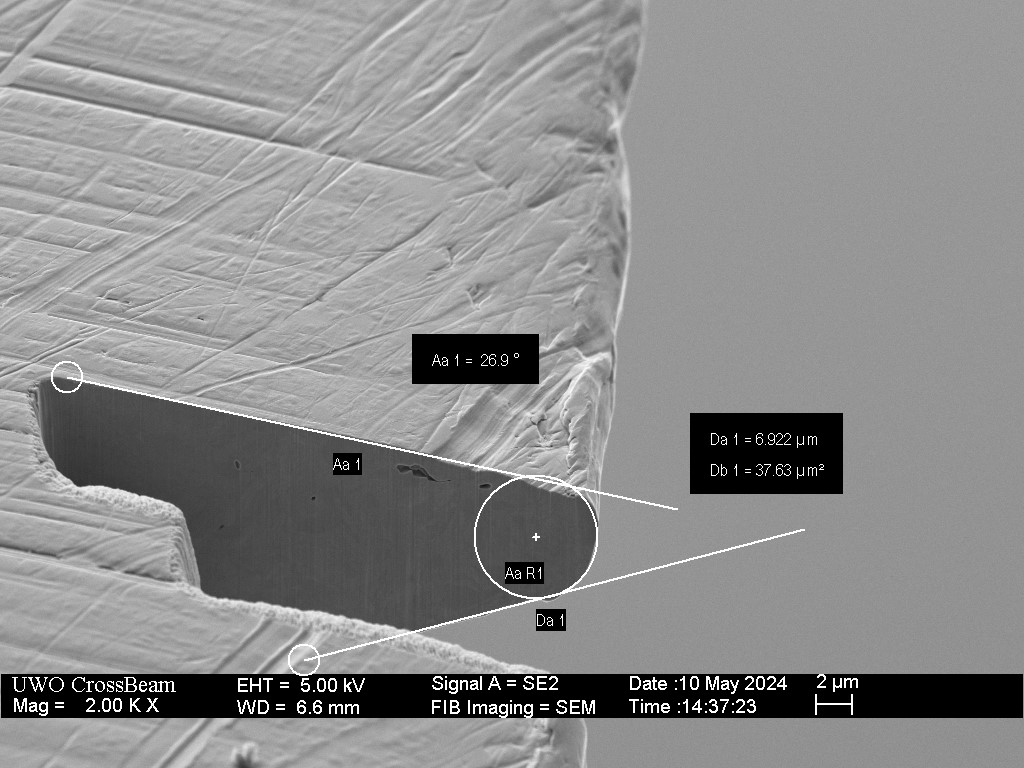

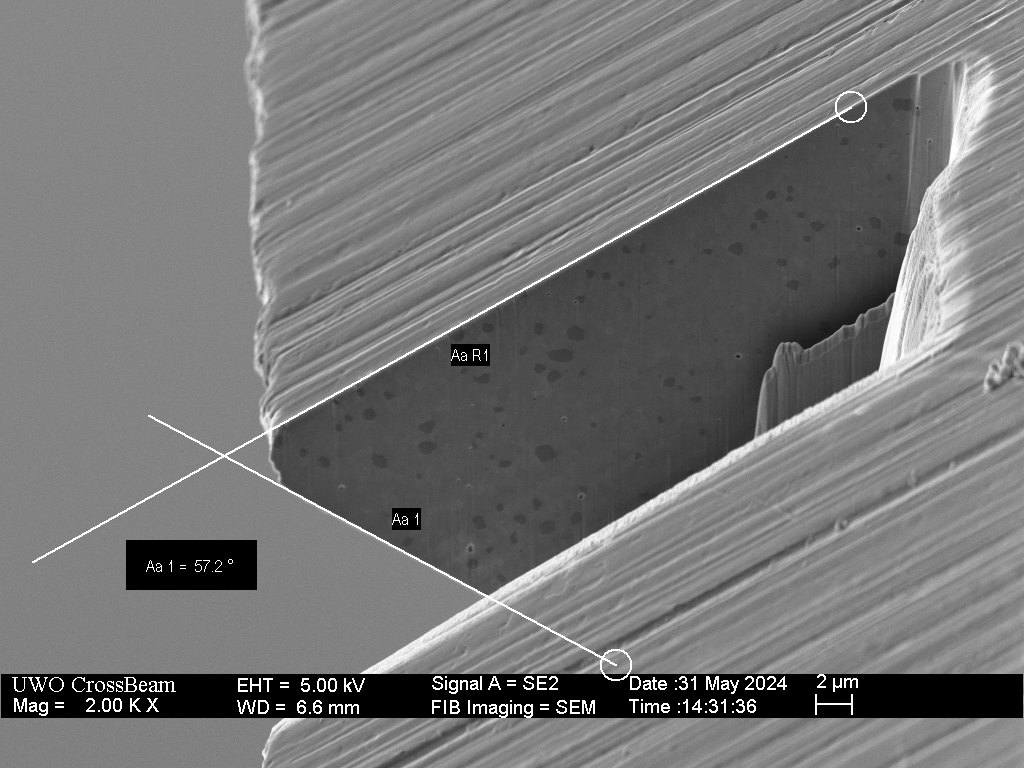

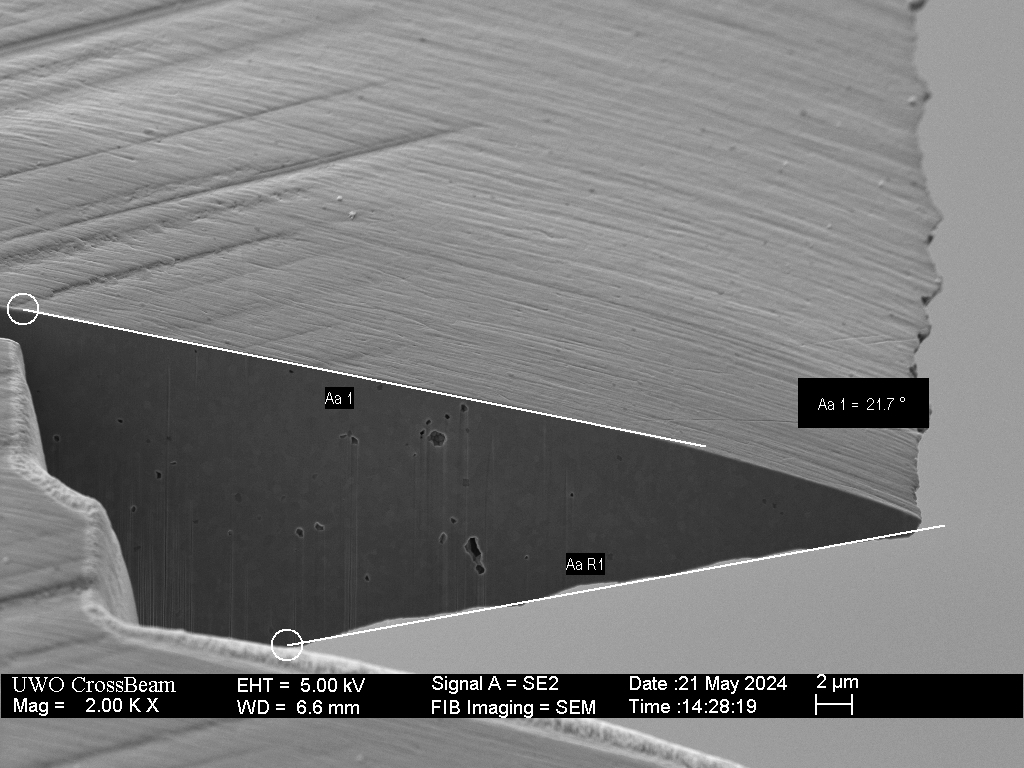

Although the blade stock is only about 1.6mm thick, this knife was nearly 1mm thick at the top of the bevel (thickness behind the edge) and that (symmetrical) bevel was sharpened at approximately 25 degrees per side, convexing to nearly 57 degrees inclusive near the apex. The factory edge radius was more than two microns. Anecdotally, these knives were unacceptably dull, unable to even dice potatoes without unreasonable effort.

As a quick test of the durability of Rahven factory edge, I again used a short section of the blade to draw cut 10 meters of corrugated cardboard. Another section was used to make 100 cuts into 3/8 inch sisal rope. The factory edge was unable to completely sever the rope. Some subtle blunting and smoothing is observed in the images below, but otherwise minimal deterioration to the already poorly performing factory edge occurred.

In my opinion the sharpening angles on these HIC knives are obscenely high. I have no information about why Rahven and Spyderco chose these angles, but for comparison, I purchased a new Kyocera “Revolution” paring knife (standard YSZ, not one of the new offerings). This knife was factory sharpened with microbevels at only 22 degrees (inclusive) and less than 30 degrees inclusive near the apex. The edge radius was less than one micron. Kyocera has taken advantage of the fact that the material does not form a burr and only stropped on one side to minimize angle increase due to micro-convexity. As expected, this knife profoundly outperforms the Spyderco and Rahven knives.

As a preliminary indication of how the low angle geometry of the Kyocera yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) knife compares, I used a small length of the blade to cut the same a amount (10 meters) of corrugated cardboard to provide a comparison with both the factory and thinned HIC knife edges and the steel NT utility knife show earlier. I know from past experience that this cutting test is sufficient to significantly blunt a fine razor-like edge on a steel knife, as demonstrated again here with the NT cutter blade.

The Kyocera knife, with it’s acute factory edge, was used to cut 10 meters of corrugated cardboard (against the grain) and re-imaged. The blade performed well even at the end of this test, undeniably better than the HIC knives did at the start, simply because of the thin and acute geometry.

A useful comparison of the new ceramic knife materials with traditional YSZ will require a determination of the appropriate sharpening angle and finishing technique. It is pointless to compare blades sharpened with different geometries. Considering that the YSZ Kyocera demonstrates acceptable edge retention even with a sub-30 degree (inclusive) geometry, the Rahven HIC must be be thinned to at least 25 degrees (inclusive) before any finishing techniques can be evaluated.

I purchased 1/2″ x 12″ diamond belts for my WorkSharp KTS MK.2, but these were incapable of thinning the knives. With the the small size and belt flexing I was unable to produce an apex less than 20 degrees per side. Perhaps if 1″x18″ diamond belts were readily and affordably available for the blade grinding attachment it would be possible to keep the angle sufficiently low, but I expect the rapid wear of these belts would still make it impractical.

After evaluating my available options for sharpening I determined that hand thinning on the Atoma 140 plate, at around 12 degrees per side, followed by sharpening with the 1/2 x 12″ 180 grit diamond belt at as low angle as possible on the Worksharp WTS MK.2 produced a satisfactory edge. I have thinned/sharpened the 5 remaining knives by this method and will be using them in my kitchen for longer term testing.

From the perspective of my efforts to understand knife sharpening, ceramic knives are interesting because they do not form a burr. I have known for some time that burrs play a pivotal role in sharpening steel blades and the presence of small, undetectable burrs can dominate the cutting performance and sharpening behavior, sometimes more so than does the geometry of the underlying bevel. For example, I suspect undetected burrs have contributed to the unfortunate trend towards ever higher sharpening angles. From a scientific perspective, this is a difficult concept to demonstrate. Overall, the comparison of ceramic and steel knives can be helpful in building a better understanding of the roll of the burr.

Initially, the goal of this series of experiments was to evaluate the the new generation of yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ); high impact ceramic(HIC). The results presented here have led me to conclude that the factory sharpening of the two knives I received were performed at too obtuse an angle. The HIC material does not behave differently from traditional YSZ ceramic – neither material will hold a keen razor-like edge. However, as demonstrated by the Kyocera YSZ knife, sharpening with thin geometry and microscopically rough apex produces a well-performing knife with acceptable edge retention. Kyocera’s approach embraces the behaviour of the material, while the obtuse grinding performed by Spyderco and Rahven attempts to avoid it. It is possible that I will revisit this material in the future; however, I have presented sufficient information here for anyone who is interested to pursue the comparison of the HIC and YSV knives.

10 responses to “High Impact Ceramic”

Fascinating. Thank you!

LikeLike

Is it possible that keen edges on these Ceramics may only possible using some other mass production industrial method? Such as some form of chemical sharpening, some sort of cleaving, or precision mold during manufacturing. I have no idea, really. This is my rare attempt at truly thinking outside the box. Interesting as always.

Now, I’m eager to learn how in the heck these things are made in the first place.

LikeLike

LikeLike

Excellent, as always…

LikeLike

Thank you for a wonderful report!

LikeLike

Beautiful work. Great images. Very Interesting.

LikeLike

Very interesting. Thank you!

LikeLike

I’ve had great success using diamond lapping films while freehanding ceramic blades, both HIC and traditional ceramic. I was able to achieve inconsistent hair whittling with my Spyderco HIC knife when using 0.5 and 0.1 micron lapping films from KME. I’m certain my results could be improved with the use of a guided system, but I’m frankly too lazy to set it up.

LikeLike

Did they use direct crack length measurement technique? DCM may lead to overestimated toughness values.

LikeLike

The value of 15MPa.M1/2 was determined by DCM (ISO 14627)

https://www.zirpro.com/files/2486/view

LikeLike